22 ways of looking at 'The Lottery'

Shirley Jackson's shocker is the second story in our classic-short-stories club

Jan on reading ‘The Lottery’ as a teenager

© 2025 Janice Harayda. All rights reserved.

When did you first read “The Lottery”? I was about 13 years old when a teacher assigned it to my English class in a good school system in a New Jersey suburb.

We’d read classic horror stories like Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Pit and Pendulum.” But none had the impact of Shirley Jackson’s tale of small-town residents who draw lots to decide which of their neighbors to stone to death.

Back then, the power of “The Lottery” came mainly from its shock value. Poe’s tales clearly belonged to a different era, but the events of Jackson’s—or so it seemed to eighth graders—might have happened in a time and place not far from ours.

I was startled, when I reread the story decades later, by how much I’d missed. By then I’d become a book critic attuned to subtexts and symbolism. And yet, I’d somehow failed to note the obvious: The men drew the lots, and the victim was a woman.

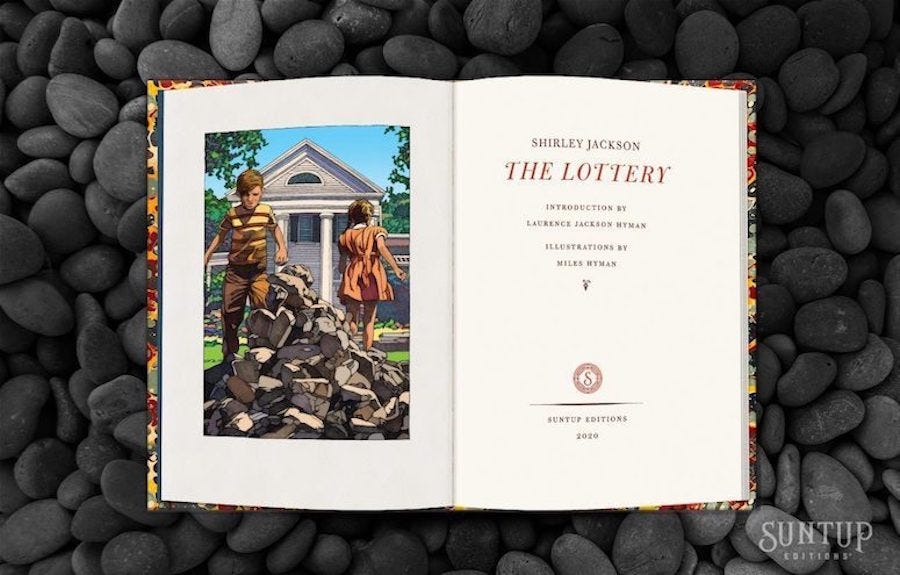

Was the story a commentary on the role of women in Jackson’s mid-century America? Or was something else going on? You can read the story here or try the award-winning graphic adaptation by Jackson’s grandson, Miles Hyman, from Suntup Editions.

In her notes below,

lists 22 ways people have characterized the story since it first appeared in The New Yorker in 1948. Susan also gives background on Jackson and what critics and others have said of her.Why not leave a comment on which interpretations do—or don’t—make sense to you? This is the second “meeting” our monthly classic-short-stories discussion club, and we hope you’ll return for the third in June.

--Jan Harayda

Susan on other ways of viewing the story

© 2025 Susan Lowell. All rights reserved.

What is “The Lottery”?

Is it the “most terrifying story ever written,” as it’s described in a headline to a YouTube video version of the story?

Or is it something else? How would you describe it? Here’s a set of interpretations, summarized from various scholars and critics as well Ruth Franklin’s excellent biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (Norton, 2016).

The most controversial story ever published in The New Yorker

An example of regional fiction

A non-regional, universal story

A lesson about the dangers of rigid rules and blind conformity

A comment on human sacrifice

A feminist parable

A protest against capital punishment

An autobiographical scream for help

American Gothic fiction in the tradition of Poe, Hawthorne, and James

An excellent choice for a high school English textbook

An allegory

An exposé of the evil that lurks in the heart of man

A beautifully structured piece of mystery fiction

A scandal

Dark humor

A reference to Hitler’s Germany

A reaction to living under the shadow of the Bomb

A banned text in South Africa, where stoning was still practiced

A Marxist attack on traditional social order

A biting satire of small-town life

A classic

Who was Shirley Jackson (1916-1965)?

A major American fiction writer (published in the New Yorker)

A minor humor author (published in Charm)

A traditional faculty wife and mom of four kids

A miserable victim crushed by the cruelty of her mother and husband

A happy housewife with a hobby

A tortured artist

A dabbler in black magic

A master of domestic horror and homey evil

A great American writer

What has been said of Shirley Jackson?

“She writes with a broomstick instead of a pen.” (Multiple critics)

“A rather haunted woman.” (Roger Strauss, her publisher)

“Even ‘The Lottery’ wounds you just once and once only.” (Harold Bloom, Yale professor)

“Like Pluto, she’s an interesting flyby but not quite a planet.” (Dwight Garner, book critic for the New York Times)

“Dad and I did not care at all for your story [‘The Lottery”] …Why don’t you write something to cheer people up?” (Her mother, quoted in Come Along with Me)

What did Shirley Jackson say?

“[In ‘The Lottery’] I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village, to shock the story’s readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity of their own lives.” (San Francisco Chronicle, July 22, 1948)

“The number of people who expected Mrs. Hutchinson to win a Bendix washing machine at the end [of the story] would surprise you.” (Quoted in The New Yorker)

Interviewer: “You were encouraged to write by your family?”

Shirley Jackson: “They couldn’t stop me” (Quoted in Ruth Franklin’s biography)

—Susan Lowell

You’ll find more here about Susan, winner of the Milkweed Editions National Fiction Award for her Ganado Red: A Novella and Stories and the George Garrett Fiction Prize for her collection, Two Desperados: Stories. Jan is an award-winning critic and journalist in a small town in Alabama.

Did you miss Susan and Jan’s comments on Anton Chekhov’s “The Bishop,” the first story read by our classic-short-stories club? You’ll find them here.

We read it in grade school! I was already such a misanthrope by then that it struck me as, "Yes, this does seem like something some people would do."

Nothing has happened to raise my opinion of the bottom third of humanity since then. We will do the most amazingly horrible things as long as everyone else seems to be OK with it.

"We Have Always Lived in the Castle" is even better.

I like it best of all of Jackson's work that I have read. It's been a while but I remember her describing a search for something in her house, or an explanation for how something had happened, that's considered peerless in its capturing the sheer madness of domestic life with young children.