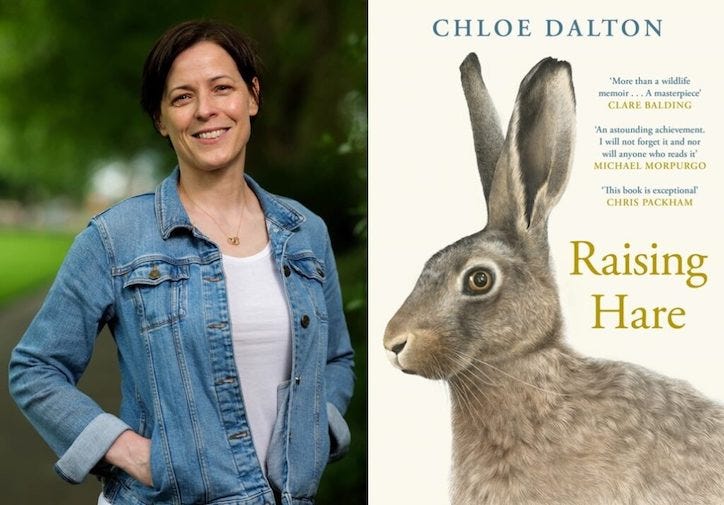

Book of the Week: 'Raising Hare'

Chloe Dalton’s graceful memoir of her life with an abandoned animal is a finalist for the Women’s Prize for nonfiction

Blame it on Marley & Me. A cliché has infested animal stories ever since the arrival of John Grogan’s entertaining memoir of an over-the-top dog that shredded furniture and ate part of his wife’s pregnancy test.

The cloying truism says that you can’t tell such tales straight up. You must reveal what you supposedly “learned” from an animal, or what it “taught” you about life or love. This device lets publishers bill books as “heartwarming,” which often translates to: “sappy” or “a great test for your gag reflex.”

Grogan set the tone when he wrote in Marley & Me:

“Marley taught me about living each day with unbridled exuberance and joy, about seizing the moment and following your heart. He taught me to appreciate the simple things—a walk in the woods, a fresh snowfall, a nap in a shaft of winter sunlight.”

You’ll find sentiments like those—often in nearly those exact words—in countless memoirs of life with a dog, cat, or other creature. Authors who insist they have “rescued” rather than “adopted” an animal often say, “I was rescued by my rescue pet,” a line popular enough to emblazon T-shirts, tote bags, and throw pillows on Etsy.

There is apparently no creature so dumb that it is presumed to have no pearls of wisdom to impart to us, as you will discover if you search online for “what I learned from my hamster.”

A bestseller in Britain and America

Yet if they descend at times into overfamiliar tropes, such memoirs can shine if their authors tell a unique story well. The latest example is Chloe Dalton’s graceful and intelligent Raising Hare, a bestseller in Britain and America and a finalist for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Nonfiction that you don’t need an XX chromosome to enjoy.

For years Dalton had worked as political adviser and speechwriter for high-octane British parliamentarians, apparently including William Hague, the former foreign secretary and new chancellor of her alma mater, Oxford University.

Then, she says, a chance encounter with an animal rerouted her daily habits.

On a February day early in the pandemic, Dalton was working remotely when she found an abandoned baby hare, known as a leveret, on a two-lane dirt track near her house, a renovated low stone barn in the English countryside.

Hesitant to interfere with nature, Dalton waited for a few hours. When the mother failed to reclaim the leveret, she concluded reasonably that it risked being struck by a car or killed by foxes or the buzzards circling overhead.

Dalton took home the hare, which had silky ears, dark brown fur, and fuzzy soles on its paws. It fit into the palm of her hand and weighed less than four ounces on her kitchen scale. She bottle-fed it, hare-proofed her house, and sought advice from a vet and conservationist, intending to release the animal into the wild when it could survive on its own.

Like Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, who won’t name a cat she doesn’t plan to keep, Dalton wouldn’t name her hare. To do so, she believed, would be to cast it as a pet, and to take something away from it. Nor did she try to tame the hare or to cage it after an alarming early experiment persuaded her to let it roam freely in her house and walled garden.

A hare that climbed into the author’s lap

But if Dalton planned only to foster the animal, the hare had other ideas. It cleaved to her and treated her home as a private extended-stay motel. The hare climbed into her lap when it wanted a bottle, sat under her chair as she worked, and slept under her bed, wrapping itself in the fold of a duvet.

As it matured, it disappeared over the top of her garden wall at night but reappeared by her door every morning, looking for breakfast.

When Covid lockdowns ended and Dalton returned to work in London, she stayed as loyal to the hare as it was to her. She watched its antics by camera while traveling in America after recruiting her mother to come by and feed the leveret its favorite meal of porridge oats.

Dalton realized how attached the hare had become to its adopted home after a business trip to the Middle East. In her absence, it had given birth to three infants in her garden. She had firsthand evidence a rare biological trait: Hares are among the few species capable of “superfetation,” or carrying two litters at once.

The newborn leverets drifted away as they matured, but their mother stayed. And Dalton had something like an epiphany after the hare had capably launched its young into the world.

“When I first found the mother hair as a leveret, I had thought of it as a creature that depended on me, as perhaps it did for the first few weeks of its life,” she writes. “But I knew now that she had everything necessary for her own care, survival and indeed reproduction. She needed nothing from me other than that I do her no harm, which might serve as a motto for all wild animals.”

No mention of Bugs Bunny

Dalton invests the hare with endearing traits without anthropomorphizing it, and she gives its species a context in history, literature, and folklore, though one light on pop cultural references. How could her book have omitted the world’s most famous hare, Bugs Bunny, whose long ears and buck teeth exaggerate prominent traits of the species? All of this is much enhanced by illustrations by the Irish artist Denise Nestor, whose finely detailed drawings are realistic and expressive without descending into a fatal cuteness.

Late in the book, Dalton forfeits some of her credibility when she begins to echo faintly all those post-Marley stories that sum up the wisdom their authors say they have gained from an animal. Her years with the hare, she says, brought lessons, including: “She has taught me patience.”

It sounds pretty, but Dalton surely must have learned something about patience while observing the political brawls among Leavers and Remainers over Brexit and other hurly-burly in Westminster. If so, she isn’t letting on.

Dalton is even less persuasive when she says straight-facedly that the hare “has made me consider the dignity and persuasiveness of silence.”

At that point, anyone with the dimmest familiarity with British politics may want to shout: “Really, Ms. Dalton? You didn’t consider ‘the dignity and persuasiveness of silence’ when Boris Johnson told the British people that no forbidden party had taken place at No. 10 during a lockdown? Why, exactly, did Liz Truss succeed him as prime minister, anyway? And why did Rishi Sunak replace Truss after just 44 days?”

It is soothing, as Dalton says, to interact with a sweet animal. But it defies belief that she learned nothing about the virtues of silence and dignity during one of the most tumultuous periods in recent British history.

Successful political speechwriters like Dalton are experts on channeling their bosses’ ideas. And some of the concluding passages of Raising Hare sound as though she has channeled too eagerly the words of an agent or editor who urged her to take her cues from the Marley clones instead of her own instincts.

But by then, few readers are likely to mind. They’ll be hooked on her elegant story of an animal neglected amid the boom in memoirs of cats, dogs, and birds. Dalton says she came to feel “unabashed love” for the mother hare and her young, and as she describes a tiny leveret, fearlessly lying under a plum tree and washing its face in a pelting rain, readers will understand why.

Jan is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book columnist for Glamour, the book editor of a large newspaper, and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle. She has written for many major media and is “Rising” on Substack, or so the platform says.

You might like my review of another finalist for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Nonfiction, Rachel Clarke’s remarkable story of a 9-year-old boy’s heart transplant, The Story of a Heart. And please check out the monthly classic-short-stories book club I’m co-leading on Substack with the award-winning writer

.We’d love to have you jump into the conversation about our first selection: Anton Chekhov’s great Easter story, “The Bishop.”