Do sensitivity readers for books go too far?

Some editors and publishers say these new 'cultural police' have too much power, and they're clipping their wings

You might think I’d rejoice if publishers hired consultants to purge their books of hapless stereotypes of women, blondes, and people from New Jersey. It’s not just that I hold lifetime memberships in all those groups. As a critic, I’ve railed for years against their unfair portrayals by authors.

Who wants to see more women depicted as weak or prey to their roiling hormones? Or another blonde portrayed as dumb or ditsy? Or a fictional character from New Jersey who says “Joisey” when people are more likely to speak that way in Brooklyn than in my native state?

I’ve seen all of those way too often in books for children or adults. But I don’t want publishers to hire specialists dedicated to eradicating them. With censorship on the rise worldwide, freedom of speech faces enough threats without adding such Orwellian limits.

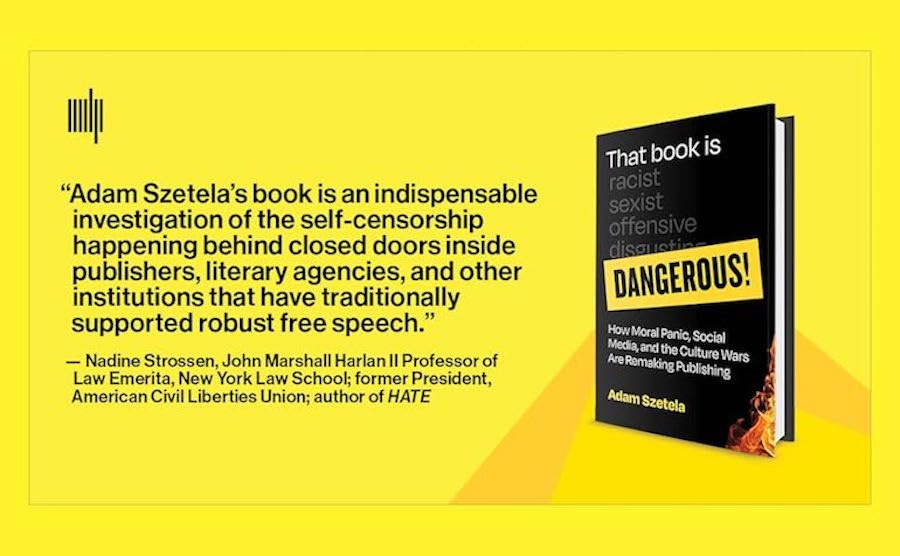

Yet something similar is happening in book publishing, the progressive journalist Adam Szetela shows in his new That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing (MIT Press, 2025). His spirited book exposes the many ways pressures from the left are curbing what people read, particularly in young adult literature.

Szetela granted anonymity to a wealth of power players in the industry: presidents of Big Five publishers, heavy-hitting literary agents, award-winning authors, and more. That range of in-the-trenches sources gives his book a rare depth and credibility on its topic in addition to a tone that, for a book from a scholarly press, is unusually lively and conversational.

In the battles over books, right-wing crusaders have had more impact on legislatures and statehouses, Szetela rightly argues. In my town in Alabama, where I now live, the public library recently lost its state funding because it refused to bow to the demands of the politicians up in Montgomery to move certain books to different shelves.

But left-wing moral vigilantes have had more influence inside publishing houses, literary agencies, and other bookish precincts. In a recent interview with Publishers Weekly, Szetela ascribed their crusades to political defeat.

“You may not be able to stop Donald Trump, the Supreme Court, the House, the Senate, and the majority of state legislatures—all of which are controlled by the right—but you can stop the publication of that ‘racist’ romance novel,” he told PW.

Some of the fiercest warriors in such battles are a comparatively new breed of self-styled experts known as “sensitivity” or “authenticity” readers.

Sensitivity readers are paid consultants hired by editors, agents, or others to vet manuscripts for words or images that might offend people who share their identity. They say there’s no substitute for “lived experience”—a cliché they helped to popularize—and they draw on their own in an effort to root out potentially offensive portrayals of often-misrepresented groups, such as black, Asian, Native American, LGBTQ, or neurodivergent characters, or people with disabilities.

The trend began about 15 years ago after advance reader’s editions of Keira Drake’s young adult fantasy novel The Continent infuriated online reviewers who saw it as a “white savior” narrative. Its publisher sent the book to sensitivity readers, whose comments led to changes before its release.

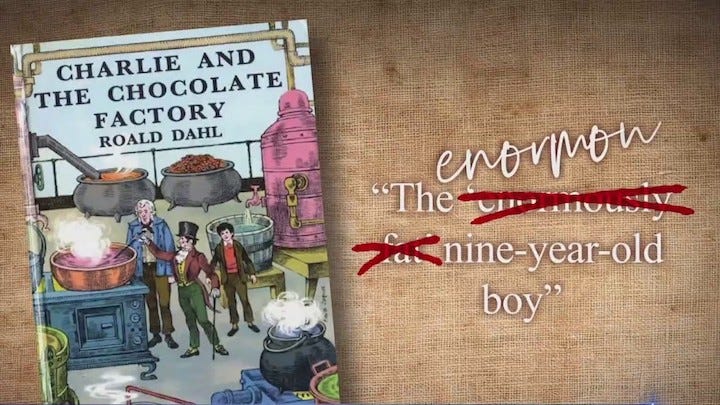

Most Big Five publishers today hire such readers at times, as do many smaller presses and agents and authors. But how they work remains little known outside the industry. Their efforts spark controversy mainly when their bowdlerization of a famous author’s work makes headlines.

A prominent example occurred two years ago when outrage erupted after a publisher removed every use of the word “fat” from Roald Dahl’s novels. Since then, such changes have become common but have flown largely under the radar.

In That Book Is Dangerous! Szetela pulls back the curtain on how sensitivity readers work and why some publishers are clipping their wings. At the heart of their work lies an effort to make books more “authentic.” But who decides what’s “authentic”? Too often, it’s not the author, Szetela shows.

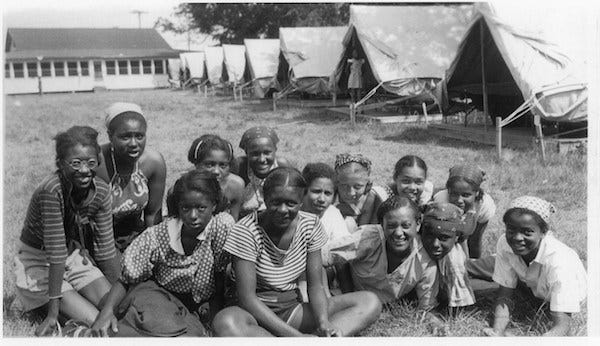

Let’s you’re a black author whose memoir describes a family visit to a national park, or who fictionalizes the trip in a young adult novel. You might hear from a sensitivity reader that you couldn’t say that because “black people don’t go to national parks.”

Does that sound absurd? It’s happened. One sensitivity reader told an author she had to change an account of black child’s visit to a national park because “going to national parks is not a thing we do as a group.” She added that “if this little girl loves to camp, you need to figure out how that happened, how her passion was stoked, how her parents and grandparents felt about it. Or you have to make her white.”

Behind that bizarre advice lies a historical truth: Black people could legally be denied admission to national parks under Jim Crow laws until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal, and their attendance remains low. About 23% percent of visitors to the parks were people of color, according to the latest 10-year survey by the National Park Service, and other studies suggest that it could be a fraction of that. Even so, that’s a long way from what the sensitivity reader implied: that black visitors never go there.

What’s happening, Szetela argues, is that sensitivity readers are claiming that there are “authentic” and “inauthentic” ways to be black, gay, trans, neurodivergent, or—who knows?—maybe a native of New Jersey.

“Sensitivity readers are so popular that some agents and publishers require them before they will even look at a manuscript,” Szetela writes.

That means authors, even if they write, say, science fiction set in outer space, must have their manuscripts vetted by someone with a background an agent or publisher views as “authentic,” at a cost that typically begins at about $250 per book. If so, Szetela writes:

“To be authentic, a sensitivity reader must share an identity with an author’s fictional character. For example, a heterosexual Chinese American author who plans to write a story about a gay Native American should hire a gay Native American sensitivity reader.”

That reality can put authors, editors, and others in a bind if there are few readily available sensitivity readers with the required identity. It can also can create a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation for writers.

One agent told Szetela that some publishers will fault you if your characters aren’t diverse. Yet if you write outside of your “lived experience,” “you’re slammed for doing that.”

Some of the pressures result from good intentions gone awry. Publishers wanted to make books more “inclusive.” But 84 percent of the people in their industry are white, Publishers Weekly has reported, and they hoped to avoid missteps in books about others.

A lack of diversity has perhaps its highest stakes in young people’s literature. Books with few or no minority characters, or that portray them stereotypically, can keep children and teenagers from reading or seeing the value of their own experiences. They can also limit their ability to understand lives unlike their own.

Yet the push for diversity has created its own problems. The fear of running afoul of it can lead to self-censorship by authors and keep them from taking the risks needed to grow as writers. Controversies about “authenticity” can put them off great writers.

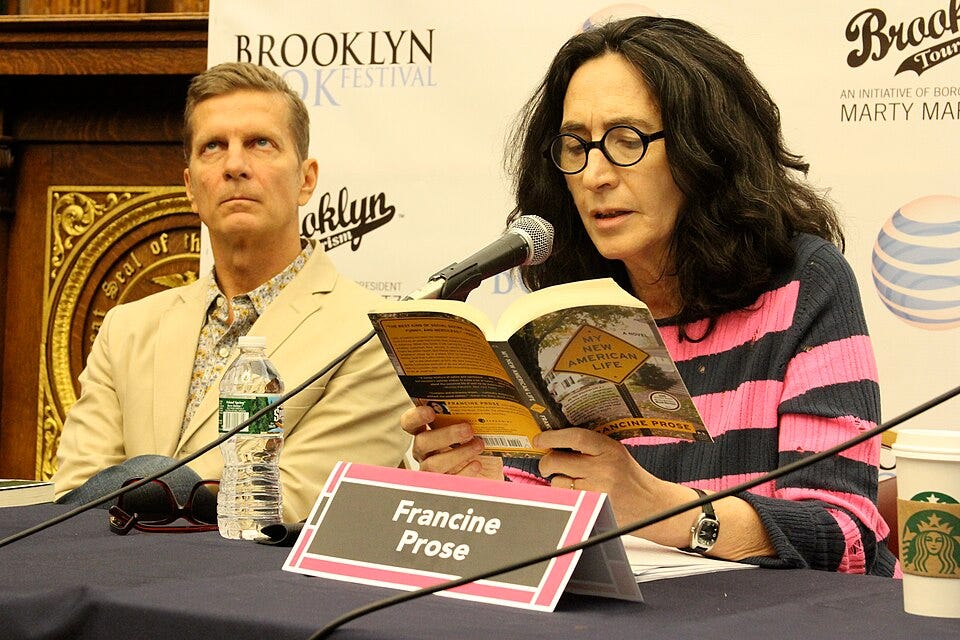

Francine Prose, the author and former president of the PEN American Center, summed up the issue an article for the New York Review of Books:

“Should we dismiss Madame Bovary because Flaubert lacked ‘lived experience’ of what it meant to be a restless provincial housewife? Can we no longer read Othello because Shakespeare wasn’t black?”

Another problem is that there’s no formal certification process for sensitivity readers. Anyone can set up shop and do it with little or no training. Szetela writes:

“These industry professionals have also eroded the idea that expertise is something a person attains, rather than something a person self-declares”:

“As a result, authors are being told their stories are not ‘authentic’ or ‘accurate’ enough to be published. Ironically, many of these authors are authors of color who write stories about characters of color.”

Some industry power players believe sensitivity readers go too far and are pushing back. One Big Five publisher told Szetela:

“The sensitivity readers we’re employing are at the very, very, very farthest edges of the cultural police. They are overvigilant to a large degree. I’ve seen some editors push back hard against what they recommend.”

The Big Five president who called readers “overvigilant” gave an example of a misguided sensitivity reader’s report:

“We had a book written by a gay man for other gay man—very, very explicitly. The sensitivity reader went through it with a flying, fine-toothed comb, and sort of added all the other categories of queerness. Every time he said, ‘gay’ or ‘gay men,’ she would add, you know, every other category of queerness and difference into it. In a way, it completely invalidated the book. It lost its point. It was absolutely specific to a certain generation of gay men.”

The CEO adds that the author, who was himself “extremely sensitive” to LGBTQ issues, balked at the proposed changes:

“We had to reject the sensitivity report completely.”

Authors, too, are resisting. Some complain that sensitivity readers treat adults like babies too dim to grasp that they shouldn’t speak like or act like characters in an 18th-century novel.

A few gaps exist in the otherwise timely and well-informed That Book Is Dangerous! Szetela doesn’t delve into the considerable effect the pressures from the left are having on publishing-adjacent areas, such as literary awards other than the Lambdas for LGBTQ books. Nor does he deal with how artificial intelligence is reshaping efforts to purge books of objectionable content. Authors say some publishers are already using AI to vet manuscripts instead of sensitivity readers. Will ChatGPT and Perplexity soon take over all of their work?

Szetela doesn’t speculate. But he reaches a conclusion likely to remain true whether an AI or a human Claude vets a manuscript:

“When sensitive publishers hire extremely sensitive people to critique books that are already sensitively written, and written by sensitive authors who care deeply about sensitivity, one ends up with feedback that is, ironically, insensitive.”

Janice Harayda is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book editor of a large U.S. newspaper and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle.

Selected Notes:

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262049856/that-book-is-dangerous/

https://www.economist.com/culture/2025/08/21/how-publishers-became-scared-of-books

https://s2.washingtonpost.com/camp-rw/?trackId=59763fc1ade4e25d6a107d24&s=68a87f8a0a9d076bef7df652&utm_campaign=wp_book_club&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&linknum=5&linktot=72

My background: I’m an award-winning critic and journalist who’s been the book columnist for Glamour, the book editor of a large newspaper, and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle. My reviews or other articles have appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Newsweek, Salon, and many other print and online media. I’ve taught writing at two large U.S. universities and spoken at many writers’ conferences.

The purpose of Jansplaining: In this newsletter I try to show—through spirited reviews and commentary—the best and worst of books and the media. I celebrate the winners and fault the sinners in related fields, whether they’re editors, publishers, and authors or the journalists who cover them. My inspirations include Dorothy Parker, E.B. White, the late Phoebe-Lou Adams of the Atlantic, and the baseball umpire of yesteryear who said, “I calls ’em like I sees ’em.”

How you can help: I live in a small town in Alabama, and much of my income from paid subscribers goes to buy books and reading materials unavailable on a timely basis from our wonderful but limited library, which recently had all of its state funding revoked for refusing to bow to the demands of pressure groups like Moms for Liberty. When that happens, you help to support not just my work but that of the authors whose books I buy in order to review them here. Thank you!

Is there a kind of "experience" different from "lived experience"?

"Unlived experience"? Like the undead?

I'm reading this book right now. It's something I spend a lot of time thinking about. There are real right-wing threats to books, real censorship.

But it's almost like that fact allows people on the left (including me) to ignore the trouble in our own backyard. It does seem like a lot of these controversies erupt online, which allows for people who've never even read a particular book to suddenly have a take so they can signal which side they are on. It's all about making sure they say the right thing at the right time, lest they be considered a traitor to the cause, whatever that cause may be.

I am specifically thinking of that weird thing that happened with Lauren Hough a couple of years ago when she tried to defend her friend's book before it was even available to read, and she got caught up in the crossfire and was removed from consideration for the Lambda literary award. And what she basically said was, hey guys, read the book first.