George Washington's sex life and more little-known history

5 questions answered by Rick Atkinson's stellar 'The British Are Coming'

Did George Washington suffer defeats in the bedroom as well as on battlefields? You might wonder after reading The British Are Coming, the stellar first volume in the Revolution Trilogy by the journalist-turned-historian Rick Atkinson.

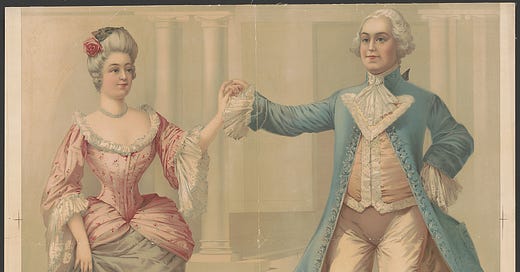

George Washington married Virginia’s richest widow, Martha Dandridge Custis, in 1759, and they seemed happy together.

“She provided intimacy for a man with few intimates, addressing him privately as ‘my love,’ ” Atkinson writes.

But they had no children, though Martha had four from her first marriage. And George may have believed their sex life needed help.

In early 1776, Martha joined him in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he was serving as commander of the Continental Army. Atkinson says George ordered a curtained four-poster bed before her arrival, and after they had married 16 years earlier, “his first requisition from a London merchant had included Spanish fly, an aphrodisiac made from crushed beetles.”

Whether that supposed love potion did any good is doubtful. In rare cases, Spanish fly can cause priapism, an unusually long-lasting erection has contributed to its reputation as an aphrodisiac.

Spanish fly can also lead to nausea, seizures, heart trouble, and other medical problems that can be fatal. Atkinson doesn’t say so, but Americans may be lucky that their first president survived not just the 3,059 days of the Revolutionary War but ingesting potentially lethal blister beetles.

Atkinson says no more about Washington’s romantic life and doesn’t speculate about it. But the anecdote suggests one of his surpassing talents: a pictorial gift that makes you see familiar people and places afresh. His work exposes a flaw in that overworked advice to authors, “show, don’t tell”: Great writers do both simultaneously.

In The British Are Coming, Atkinson distills his vast research into a story that moves swiftly. Good popular histories often have a stop-and-go pace, pausing the action for set pieces that stand still.

Atkinson avoids that drawback by weaving vital facts into his story. He has a singular talent for finding apt quotes, rebutting myths without becoming pedantic, and setting a vivid scene. If he’s describing an event such as Washington’s Christmas-night crossing of the Delaware, you’ll know the color of Washington’s horse (sorrel), the countersign or secret words used to verify an ally’s identity (“victory or death”), and what the weather was (so cold two soldiers who lagged behind others froze to death after falling the ground).

Here are some questions his book answers.

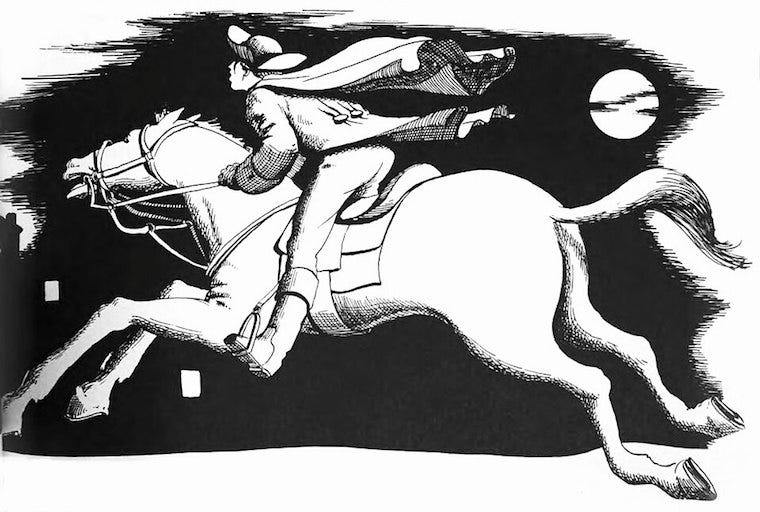

Did Paul Revere really say, ‘The British are coming’?

“On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five: / Hardly a man is now alive / Who remembers that famous day and year.” Maybe Henry Wadsworth Longfellow should have added, in “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere”: “Or who recalls it accurately.”

Myth has it that Revere shouted “The British are coming!” to warn American patriots of the impending arrival of redcoats with guns. Historians know otherwise, and Atkinson sums up the accepted view: “a witness quoted him as warning, more prosaically, ‘The regulars are coming out.’ ”

What about Nathan Hale and his famous last words?

At age 21, Capt. Nathan Hale was executed by the British after being caught spying for the Americans on Long Island. His fame today rests largely on his supposed last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

Did Hale ever say them? Atkinson finds more credible an account that says he showed great composure “and desired the spectators to be at all times prepared to meet death in whatever shape it might appear.”

Were American soldiers the ‘ragtag’ band the clichés say?

“Discipline is the soul of an army,” Washington wrote in 1757.

But he saw little of it when he took command of a Continental Army long on “barely educated” farmers or shopkeepers. For days, he rode around Boston “inspecting, correcting, fuming” before issuing another raft of orders.

“No two companies drilled alike,” Atkinson writes, “and together on parade they were described as the finest body of men ever seen out of step.”

Washington levied fines, approved floggings, and had soldiers court-martialed. And at first, it seemed to do no good.

“My difficulties thicken daily,” he wrote to patriot leader John Hancock. In The British Are Coming, Atkinson shows how—over time—he overcame many of them.

What did Washington’s early battles reveal about him?

Atkinson admires Washington but doesn’t hide his “misjudgments and shortcomings” in the years 1775–1777, those covered by The British Are Coming (Holt, 2019).

Among his most conspicuous failings: “His lieutenants had saved him from himself more than once, as when they resisted his proposal to launch a frontal assault on Boston.” But he learned from his early missteps. Atkinson writes:

“Affliction revealed Washington’s courage, durability, probity, and administrative skill. Since his appointment to lead the new army, he had developed a shrewd understanding of the refractory, independent peoples known collectively as Americans. ‘A people unused to restraint must be led,’ he wrote in January 1777, ‘they will not be drove.’ ”

Notes:

https://poets.org/poem/paul-reveres-ride

https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/paul-reveres-ride.htm

https://www.paulreverehouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Ep.-3_-What-did-PR-Actually-Say_.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8765116/

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781627790437/thebritisharecoming/

My background: I’m an award-winning critic and journalist who’s been the book columnist for Glamour, the book editor of a large newspaper, and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle. My reviews or other articles have appeared in major print and online media including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Newsweek, and Salon. I’ve taught writing as an adjunct at two large U.S. universities and spoken at many writers’ conferences.

The purpose of this newsletter: I try to show—through spirited reviews and commentary—the best and worst of books and other media in the 21st century. That means I celebrate the winners and fault the sinners in related fields, whether they’re editors, publishers, and authors or the journalists who cover them. My inspirations include Dorothy Parker, the late Phoebe-Lou Adams of the Atlantic, and the baseball umpire of yesteryear who said, “I calls ’em like I sees ’em.”

How you can help: I live in a small town in Alabama, and much of my income from paid subscribers goes to buy books and reading materials unavailable on a timely basis from our wonderful but limited library, which recently had all of its state funding revoked because it refused to bow to the demands of pressure groups like Moms for Liberty. When that happens, you’re helping to support not just my work but that of the authors whose books I buy so I can review them here. Thank you!

Timing is everything, I’ve been researching the geography of the revolutionary war and this doorstopper will be an excellent addition. As always, great writing Jan. I’ve followed you from Medium, and glad you’re here. Thanks for sharing your wisdom in delightful arenas.

And then 203 years after Spanish Fly, we got Venus Flytrap...https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQvCNLIVydM

*I had to, it was there. LOL