Letter from a Reader 9.3.25

Why book awards are out of control and losing credibility: my view as a past judge of one of America's biggest

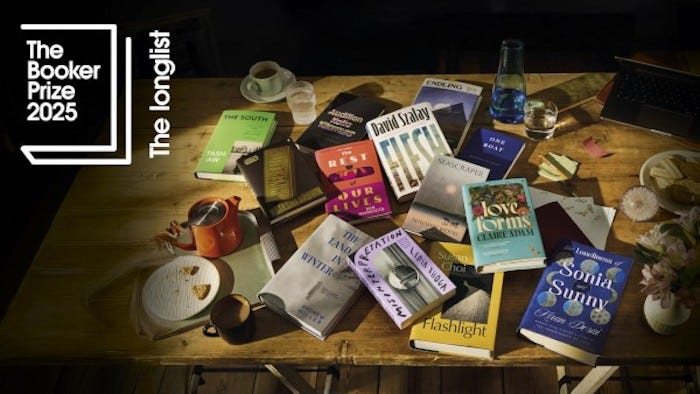

Brace yourselves, everyone. This week marks the unofficial start of that annual literary arms race, the high season for book awards.

By Thanksgiving, we’ll know who won at least a half dozen of the world’s most coveted prizes. Among them: the National Book Awards in the U.S., the Booker and Baillie Gifford prizes in the U.K., the Prix Goncourt in France, the Giller Prize in Canada, and the Nobel in Literature. As Sherlock Holmes said, in a line cribbed from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1, “the game is afoot.”

Britain fired the opening gun in the arms race when the judges for its top fiction award, the Booker, released their longlist on July 29. Its top nonfiction award, Baillie Gifford, gave chase when it revealed its longlist today. Each of those two earns the winner £50,000. After that come the longlists for National Book Awards (Sept. 9–12) and the Giller (Sept. 15), followed by a flurry of shortlists: the Booker (Sept. 23), the Baillie Gifford (Oct. 2), and the NBAs (Oct. 7).

Then the winners pile up: the Goncourt (Nov. 4), Nobel (Oct. 9), the Booker (Nov. 10), the Giller (Nov. 17), and the NBAs (Nov. 19). Those winners earn amounts ranging from a largely symbolic €10 for the Goncourt to the roughly $1 million for the Nobel. 1

That list omits the specialized awards that carry weight within their communities, such as the Lambda Literary Awards for LGBTQ books, arriving on Oct. 4. Nor does it count the year’s-best-book lists in the media, or heavyweights arriving early in 2026, including the Newbery and Caldecott Awards in January and the National Book Critics Circle Awards in March.

All of this might make you wonder: Do we really need so many book awards?

In the late 1990s, I was the vice president for awards of the National Book Critics Circle, one of the top three U.S. book awards along with the NBAs and the Pulitzers. Back then, major prizes typically announced only a shortlist of five books per prize or category before naming the winner. That ended soon after my term. The Booker began releasing a longlist in 2001 and the National Book Awards in 2013. The NBCC published its first longlist in 2024.

Some majors are also giving more prizes. The National Book Awards and the NBCC have added an award for translated literature. The Booker Prize launched an international award in 2005. Other sponsors have added even more categories or lists.

The explosion of longlists and prizes seems to have begun for an honorable reason. Too many good books, especially by women and minorities, didn’t get the recognition they deserved. By posting longlists, prize-giving organizations could bring more attention to books by unjustly neglected groups. They could also show that they had seriously considered certain books, whether or not they won top honors.

But the good intentions had drawbacks that persist. Adding awards or longlists increases judges’ workloads unless prize-givers also expand the number of jurors. The risks are rising now that more books—and potential contenders for prizes—are published every year. If judges are overwhelmed by their responsibilities, the quality and credibility of their awards, if not their importance to authors, may suffer.

The NBAs take at least $100,000 from Penguin Random House

Nothing makes the dangers clearer than the translated literature prize added in 2018 by the National Book Awards, a perennial swamp of conflicts of interests.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Jansplaining to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.