Why I quit reading Percival Everett's 'James'

My reasons go to the heart of why I read, which is for pleasure

For years I lived near the editor-in-chief of a high-prestige Random House imprint who often used the same words in rejecting a manuscript. He would tell the literary agent who had submitted the book: “It didn’t capture my heart.”

Succinct as it was, his remark came closer to the truth about how a lot of us read than longer-winded explanations involving phrases like “too little conflict” and “weak narrative arc.” We respond to books with our hearts as well as our minds.

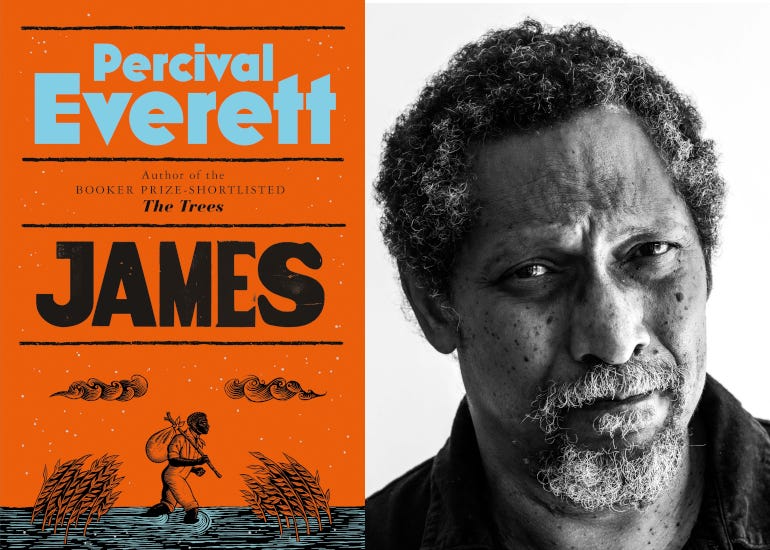

Percival Everett lately has been stealing hearts, as Jane Austen wrote in another context “Longitudinally, Perpendicularly, Diagonally,” with a recasting of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn centered on Jim instead of Huck.

Everett’s James is the 2024 Homecoming King, a bestselling National Book Award winner and Pulitzer frontrunner that has people blowing kisses from all corners of the literary stadium. His novel has won hearts more consistently than the new book by the Homecoming Queen, Sally Rooney, whose Intermezzo has inspired a deserved backlash.

I have a journalist’s instinctive skepticism of bandwagons like the one that’s made James a book club favorite. In several decades as a staff or freelance book critic, I’ve seen too many novels overpraised: Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan soap opera, My Brilliant Friend; Hilary Mantel’s lionization of Thomas Cromwell, Wolf Hall; Delia Owens’ font of racial stereotypes and romance novel clichés, Where the Crawdads Sing. I’m a Claire Keegan woman, myself.

In self-defense, before investing in a novel, I’ve been downloading the free excerpts from Amazon or a publisher’s site. For James the online text included the first two chapters and part of the third, a generous 35 or so pages.

Nothing in them captured my heart, and I’d planned to stop there.

But by happenstance, James sat on an end table when I arrived at two friends’ home for Christmas dinner, and I began flipping through it. A host, seeing my interest, said she’d dipped into the book, decided not to finish it, and offered to lend it to me.

The moment was my Annunciation. I could almost hear the Archangel Gabriel—instead of announcing the virgin birth to Mary—saying, “You need to read more of James before posting another of your jeremiads about the follies of National Book Awards judges.”

So on Christmas night—happily sated with generous hacks from an excellent cheese ball and a roast from an Ina Garten recipe—I read the last 32 pages. They were marginally better than the early chapters, chiefly in that the story was rolling by then, and they were less didactic.

But the novel was still pursuing my heart from Antarctica.

Cézanne and Rilke may have impeded its conquest. In the fall of 1907, Rilke went regularly to the Salon d’Autonne in Paris to see the paintings by Cézanne and wrote to his wife about their impact. He said in a letter to Clara:

“One could really see all of Cézanne’s pictures in two or three well-chosen examples.”

Something similar is often true of novels: You can see all of the author’s work in two or three apt examples, and the candidates turned up early in James.

Survival lessons for enslaved children

In a chapter you get if you click on “Send a Free Sample” on Amazon, James teaches enslaved black children how to speak “correct incorrect grammar,” such as “dat be” instead of “that is.” He explains:

“White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them.”

James says more about what “white folks” want and about the need to conform to it to survive in their world. Among it: “White people love to buy stuff.” (Who knew?) And: “There was nothing that irritated white men more than a couple of slaves laughing.” (Does that explain why Gov. George Wallace told slaves’ descendants: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”?)

James is teaching black children or, later, others to pander to white people to stay alive. But Everett seemed to pander coyly to his own readers, too, alternately lecturing and winking with a subtext bordering on a cuteness that’s fatal to literary fiction. It implies: “I know you’ll get this.”

I wasn’t reassured by a review by one of America’s most thoughtful fiction critics, Sam Sacks of the Wall Street Journal. It said tactfully that the pedagogical tone is “always somewhat present in the novel.”

White ‘guilt and pain’

There was also a whiff pandering in the faddishly short, large-font chapters of Everett’s book, a James Patterson-influenced trend that—to judge by comments I’ve seen from critics—has inspired its own pushback. There’s an irony in that format: Everett aims to show that enslaved people had more intelligence than their white owners imagined, but the brevity of the chapters at times leaves the impression James had no longer thoughts.

Everett also seemed to play anachronistically to white guilt, an idea that didn’t gain traction until James Baldwin’s 1965 essay, “The White Man’s Guilt.”

In the last chapters of his story, James muses about how much of the desire to end slavery was driven by the need “to quell and subdue white guilt and pain” rather than to end a horrific injustice.

Other critics have noted that James is aware of Kierkegaard, who didn’t have an English translation until the next century.

Anachronisms like that may represent an intentional blurring of the line between past and present, a valid literary device. But the sections on white guilt rang false to what I’ve seen in a decade in a small town in Alabama.

I live about 20 miles from the spot where Ku Klux Klan members hanged the teenage Michael Donald after murdering him in 1981, the last officially recognized lynching in America. In my time here, the Klan has strewn flyers on my street and on others in my town and its neighbors.

In my experience, such incidents keep occurring because many white residents still feel no “guilt and pain” at all about racism, let alone a need to “quell and subdue” it.

A highly skilled one-trick pony?

The more I read of James, the harder it became to suspend my disbelief or my fear that the novel would turn out to be a highly skilled one-trick pony. A book inspired by another needs to nod to the original while also transcending it and establishing its own identity. Perhaps because I’ve written so much about Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain sat distractingly on my shoulder as I read the excerpts from James.

Yet I might have persisted had my portion enabled me to see afresh the classic that inspired it. All critics do their own mental calculus about how much of a book they have to read to give it a fair shot, a math that depends factors such as the type of book and its promise.

After more than 60 pages of James, I still wondered: What was the point of going on when my heart remained a fugitive?

I read for many reasons: for truth or beauty, for insight or facts, for escape or distraction, or because a publication is paying me to do it. But above all, I read for pleasure. James, finally, yielded too little of it to keep reading.

I had other novels I wanted to read and higher literary priorities than Everett’s perspective on a racism I’d seen too much of in real life, including when the KKK threw flyers into my neighbors’ driveways. To paraphrase Huck in Twain’s masterpiece, it was time to light out for the territory of other books.

Jan Harayda is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book columnist for Glamour and the book editor of a large U.S. newspaper. She has also been a judge of the National Book Critics Circle Awards, which more recently gave Percival Everett a lifetime achievement award.

Capsule reviews of 50 of her favorite books appear in two Jansplaining for paid subscribers, “50 Novels I Like” and “50 Nonfiction Books I Like.”

Isabel Wilkerson's 'Caste' had a great quote. After giving a lecture in London, a woman who emigrated from Africa came up to her and said "I wasn't 'Black' until I came to the UK." About the most accurate description on race or anything I've read in my life.

Haven’t read James, but feel the need to come to the defense of Elena Ferrante… How many great (truly great!) novels are essentially soap opera plots written in exquisite language? A good deal of them! And Elena Ferrante is capable of such verbal precision, such profound psychological insights, such beautiful sentences. I believe she is among the greatest contemporary writers. Maybe even the greatest alive.