Why you can't trust 'year's best' book lists

8 out of 10 of the 'best' books on the New York Times list are from Penguin Random House, and that's just the beginning

Books are my drug, and when I edited the book section of a large U.S. newspaper, I was a pusher. Instead of meeting my fellow junkies on street corners, I met them in print or, thanks to a wire service that distributed my reviews, on a screen.

For 11 years, I reviewed books, assigned them to freelancers, and put the best on our weekly “Recommended” list. I also did an annual roundup of the cascade of books intended for holiday giving, such as undersized stocking stuffers and oversized art or photography doorstoppers.

Even so, like a marijuana user who won’t do heroin, I had my dignity.

I drew the line at compiling an annual list of the year’s best books. My reason for refusing to do one was simple: Most of those lists seemed — if not dishonest — inherently unfair.

My newspaper received more than 400 review copies a week from publishers in every major genre of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry for adults and children. All of those categories annually had books worthy of making a best-of-the-year list.

I didn’t have the staff to vet all the review copies that arrived, and if I’d had it, I’d still have faced Gordian-knotty questions. Which is “better”: a brilliant first novel, a Nobel laureate’s poetry collection, or a reporter’s exposé of a company dumping toxic chemicals into a small town’s water supply?

Your answer might depend on how you highly you valued fiction, poetry, and nonfiction such as journalism. Or, more to the point, how much you thought they mattered to your readers.

If you did a “year’s best books” list, as I saw it, you’d be grading on curve that involved factors other than merit. That’s partly why year’s-best book lists—unlike lists of the best new releases in other media — can misfire even at publications with larger staffs than I had. Here are other reasons why they’re untrustworthy.

1 Nobody can do justice to all the books published

Each year about a half million new books come from traditional publishers, and about two million more are self-published. Penguin Random House alone publishes more than 15,000 titles under 300 imprints.

Major print or online publications typically select their annual “best books” from among those their staff or freelance critics reviewed in the past year.

But nobody can read everything that’s published. Critics focus on the fraction of books that seem worthiest of attention.

A lot of things influence what critics see as “worthy” of reviewing: their personal tastes, the reputation of an author or publisher, the buzz or marketing for a book, and — of course — whether they’ve read any or all of a candidate. And book reviewing is a swamp of conflicts of interest.

Ross Barkan, a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine, was right when he wrote at Political Currents on Substack:

“Most critics now are freelancers, and often working novelists themselves. This sets up an obvious conflict of interest that has only worsened over the last decade as full-time critics vanish; a novelist looking to advance their own career is only going to review a new book so honestly. The reviewer understands the careerist incentives at play. Lavish praise and find a new ally. Pan a book aggressively enough and the writer’s own book, when it eventually appears, could face a similar reception.”

What all of that means is that by the time a publication does a year’s-best list, any number of worthy books may have been eliminated and unworthy ones elevated for reasons unrelated to merit. It isn’t uncommon for books to win major literary prizes such as the Pulitzer after having appeared on no year’s-best lists.

2 Books aren’t like movies, music, or TV shows

A point nobody discusses when the year-end lists arrive is: It takes far more time to read a book than to listen to a song or watch a movie or TV show.

An average song on Spotify is three minutes long. A movie takes 60-to-120 minutes, and TV show, 22 minutes or 44 minutes, depending on the genre. A 300-page novel takes me an average of 8-to-10 hours to read, or 480 minutes. You could listen to a hundred songs and watch a half dozen movies and twice that number of TV shows in the time I need to finish a book.

Movie and music or TV critics may well have seen or heard all the best candidates in field. Few book reviewers can make the same claim. That makes annual lists of the year’s “best” books less credible than those that honor other media.

3 Criteria for year’s-best lists are vague and subjective

Few publications spell out their criteria for their year’s-best book lists. When they do, their comments are unedifying. The New York Times editors summed up their criteria in a line in their clunky introduction to their 2024 list:

“Ultimately, we aim to pick the books that made lasting impressions: the stories that imprinted on our hearts and psyches, the examining of lives that deepened what we thought we already knew.”

That lead-in says nothing about looking for books that might have been “imprinted on” minds rather than “hearts or psyches.” It leaves the impression the Times editors sought books that had an emotional rather than literary, artistic, or intellectual impact.

You might wonder in any case whom their honored books made “lasting impressions” on. One of the Times’ 10 best was a selection of Jenna Bush Hager’s book club on Today. Does making a “lasting impression” on a celebrity television host count?

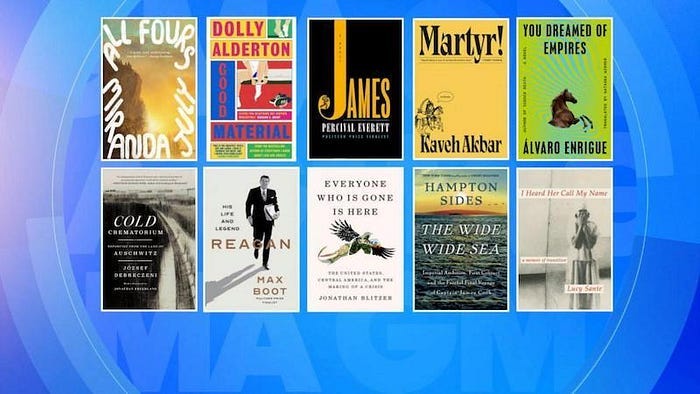

It’s also striking that eight of 10 books¹ on the Times list come from Penguin Random House imprints. Is PRH really issuing 80% of America’s best books?

Yes, PRH is the largest U.S.-based publisher (and other publishers appear on the Times’ list of 100 Notable Books). But the Wall Street Journal has only two books from PRH brands on its list. And unlike the Times, it found worthy books from Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, a university press (Chicago), and a small press (New York Review Books). Why was there so little diversity in the publishers tapped by the Times?

4 The lists are timid and predictable

Year’s-best lists are too short on books from small presses or little-known authors. They are too long on books the media have showered with attention, deserved or not.

More than half of the books on the Times’ top 10 list come from bestselling authors, some of whom have also won or been shortlisted for major U.S. or U.K. prizes. An exception is Cold Crematorium, the late Hungarian journalist József Debreczeni’s memoir of his deportation to Auschwitz and forced labor in concentration camps.

Welcome as the inclusion of that book is, the Times’ list showed such a strong bias toward heavyweight publishers that you wonder if the paper would have included it had it come from a small press rather than Hachette. Political biases may also affect the selections.

Earlier this year the Economist reported that books by conservative authors were 7% less likely appear on the New York Times bestseller list than others. Given that the Times is a liberal paper, it’s reasonable to expect its year-end lists to lean left, too.

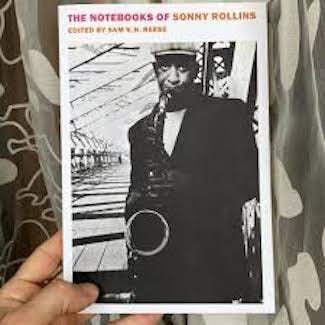

Few major media show the kind of the courage the Wall Street Journal did when it tapped for its “10 Best Books of 2024” list The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins, a collection of journal entries by a great jazz artist, edited by Sam V. H. Reese. This slim volume differs from the overwhelming majority of books on such lists in that it has received little attention, comes from a small press, and is a book in which an editor shares credit with the author. It’s perhaps ironic that the editorially conservative Journal looks more progressive than the liberal New York Times on calls like that one.

5 The lists don’t reflect how people really read

In deciding what to read, few people look for something that’s come out in the past year. They’re more likely to be influenced by word of mouth, bestseller lists or awards, the choice of their book club, or the author or subject.

That fact may be especially true of readers of literary fiction, but it also applies to others. Last year 5 of the 10 most checked-out novels in the New York Public Library system were genre fiction published before 2023: Emily Henry’s Book Lovers (2022), Colleen Hoover’s Verity (2018) and It Ends With Us (2016), and Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo (2017) and Daisy Jones and the Six (2013).

How could best-books lists be better?

Year’s-best-books lists don’t have to be what they are today: ritual hosannas that rubber-stamp bestseller lists, have undisclosed biases, or don’t reflect how people read. If you do a list, here are ways to beat the trap.

Focus on what you do best, and disclose any conflicts of interest. Some of the most credible lists come from specialists like food writers who write only about cookbooks or music critics who home in on rock-star bios and the like. You don’t owe the world your view of the new Sally Rooney novel or analysis of the rightward drift in American politics. And there’s no shame in plugging your best friend’s book if you disclose the connection.

Kill the pretense. Don’t imply that your list is definitive if it has only your favorites among the small number of books you’ve read. A good example comes from the Kyiv Independent, a young English-language site in Kyiv. Its best-books-of-2024 roundup focuses on books about Ukraine, and it doesn’t presume to be the last word. Its editors say they’ve listed “some of the best books,” not “the best,” and they call the list “a guide rather than a definitive ranking.”

List the best books you read, whether or not they came out in the preceding year. Among the most persuasive lists is the Year in Reading series on The Millions, which annually asks “some of today’s most exciting writers and thinkers” to write briefly about what they read in the past year. Britain’s the Spectator does something similar. Every year the magazine asks its regular contributors to describe briefly a few memorable books they read in the past 12 months, whether new or centuries old. It doesn’t call the result the year’s “best” books but “Books of the Year.”

Media like the Kyiv Independent show that literary highlight reels can be a service to readers that’s also stimulating and fun to read. Right now too many lists stimulate only disappointment over their unfairness to authors, publishers, and readers who’d hoped for better.

[1] The eight Penguin Random House books on the Times’ list and the PRH imprints they come from: All Fours (Riverhead), Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here (Penguin), Good Material (Knopf), I Heard Her Call My Name (Penguin), James (Doubleday), Martyr! (Knopf), The Wide Wide Sea (Doubleday), You Dreamed of Empires (Riverhead).

Jan Harayda is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book columnist for Glamour, the book critic for a large U.S. newspaper, and a vice present of the National Book Critics Circle. Her reviews or other articles have appeared in media that include the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Commonweal, and Salon.

In addition to all the free content, paid subscribes to Jansplaining have access to capsule reviews of some of her favorite books in “50 Novels I Like” and “50 Nonfiction Books I Like.”

Thank you, Leslie! One hopeful sign is that I posted this earlier on Medium, where it's had thousands of claps. And while I avoid cross-posting here, I've done it in this case because it's so disturbing that media critics aren't calling out the Times on its list.

Look forward to your list, too. It doesn't matter that you aren't a professional critic. Other writers should take a cue from you and do their own lists as a counterweight to the herd mentality that infects the lists in so many other places.

This! Is! Great! Hear, hear to everything you've written. And thanks for tackling this subject. (If you're interested. I put together an annual list of Best Books I Read that meets much of your criteria...except that I'm not a professional critic! Here it is if you're interested anyway: www.workinprogressinprogress.com