'Would Joan Didion have published this?' is the wrong question

Critics and fans have condemned a book of her notes on her psychotherapy, but they should put away their knives

In the summer of 1968, Joan Didion took several standard mental health tests at an outpatient clinic in California after suffering from vertigo and nausea. Doctors wrote afterward that she had a “pessimistic, fatalistic, and depressive” worldview and prescribed the antidepressant Elavil, an incident she wrote about The White Album.

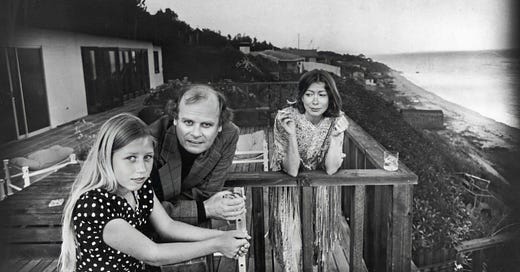

You can read Notes to John as a bookend to that report, and it’s not pretty. In 1999 Didion began seeing a prominent Freudian psychiatrist, Roger MacKinnon, after a crisis involving her daughter, Quintana. She and her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, had adopted Quintana as an infant and were unsure of how to respond to her worsening alcoholism and other woes. Didion was now taking Zoloft, another drug used to treat depression.

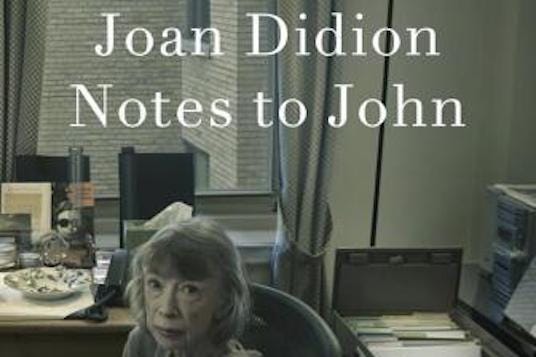

Didion typed up summaries of her conversations with her psychiatrist after each session, and they turned up in a file found by her literary executors, her agent and two editors, after her death in 2021. Forty-six appear in Notes to John, which also has an unsigned foreword and an epilogue noting that Quintana died in 2005 of a “cascade of disastrous medical events.”

The notes are nominally addressed to John, the “you” in her summaries. But they focus on Quintana’s perils, ranging from her frustrations with her own therapy to her sidelining as a photographer for Elle Décor. The notes say little about Dunne beyond making clear that the couple led lives deeply enmeshed in ways that went beyond their collaboration on screenplays for movies like “The Panic in Needle Park” and a remake of “A Star Is Born.”

Didion’s money woes, breast cancer, and more

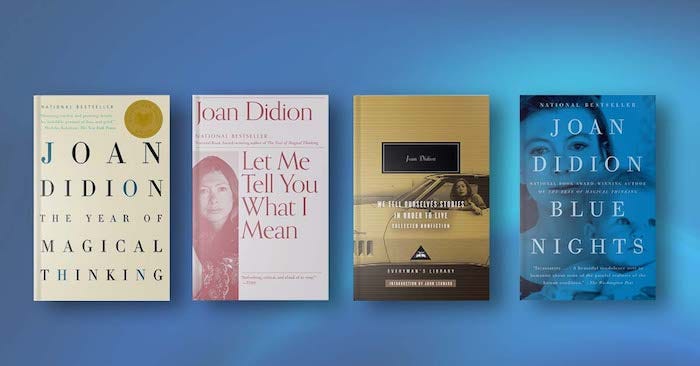

Dunne’s shadowy presence is among the aspects of Notes to John that raise questions about how much, if anything, Didion’s executors cut or edited or what she herself withheld. Dunne had a well-known temper, a career by then overshadowed by his wife’s fame, and heart trouble that would kill him in 2003 and inspire her National Book Award-winning The Year of Magical Thinking. It’s hard to believe none of this came up in therapy.

We read about instead Didion’s depression, her money worries, her earlier bout with breast cancer, her fears that Quintana might be suicidal, and—unsurprisingly given her therapy with a Freudian—far too much about her mother’s role in her upbringing.

Unleavened by the perspective of time, her notes have the flat and prosaic quality dashed-off news bulletins, not well-crafted essays. They lack her dry wit, her elegantly spare language, and her ability to situate her experiences in an edifying social context. In a word, they lack style, a quality that defines all of her published work.

Didion avoided cant and jargon and exposed their hollowness when she heard them, whether from politicians or hippies in Haight-Ashbury. Yet in Notes to John, we hear her describing her therapy as a “learning experience,” the kind of bloated language she never used in work published in her lifetime.

It’s no wonder the question “Would Didion have approved this book?” has set critics abuzz. But it’s the wrong one to ask.

Whether Didion would have wanted the book published is moot. She left no instructions about what her estate should do with her notes. But Nathaniel Rich offers a telling, retroactive clue in his foreword to her South and West. Rich says that while working on that book, she typed up her observations at the end of each day. Rich added:

“These notes represent an intermediate stage of writing, between shorthand and first draft, composed in an uncharacteristically casual, immediate style….The effect can be jarring, like seeing Grace Kelly photographed with her hair in rollers or hearing the demo tapes in which Brian Wilson experimented with alternative arrangements of ‘Good Vibrations.’ ”

Rich describes perfectly what Didion sounds like Notes to John: a literary Grace Kelly with her hair in rollers. She may not have been planning to publish her notes about her therapy, but she used the method she favored when writing a book.

MacKinnon’s comments, as transcribed by Didion, abound with banal and clichéd observations, running to lines like: “There’s typically a good deal of stress between adolescent daughters and their mothers.” At times you wonder why Didion didn’t shout: “Tell me something I don’t know.”

Who benefits from all of this besides Didion completists and the heirs and publishers who will cash in on it? Certainly Didion has given doctoral students a trove of bones they will be picking over for decades in theses and dissertations. She’s also given psychiatry departments and associations fodder for endless discussions about the layers of ethical questions raised by this book.

What about readers? Notes to John may hurt Didion with newcomers to her work who take it, mistakenly, as typical.

But Didion is too good a writer to offer no insights at all. One occurs as she and her psychiatrist discuss her fear of losing Quintana. Didion quotes MacKinnon as saying:

“You told me how sad it had made you when her friends were quoting their mothers’ favorite sayings and she said yours was ‘brush your teeth, brush your hair, shush I’m working.’”

Didion says it’s true. And she goes further, saying that “all of my fiction during her childhood could be read as an attempt to work through separation from her before it happened.”

Perhaps the greatest value of this book for Didion’s fans is that it should dispel any notions that her bleak worldview was an act. Her literary sensibility was so refined—and so carefully tended—that it’s easy to wonder if it was a pose. Had Didion created the kind of persona that led to the mythologizing of Joan Baez, “a personality before she was entirely a person,” a reality she faulted in Slouching Towards Bethlehem?

In Notes to John, her pain is too clear for that. Her emotions may lack the polish they have in memoirs like The Year of Magical Thinking. But their honesty is beyond dispute, especially when her psychiatrist urges her to stop worrying about the potential results of her efforts to help Quintana and just get on with it. Didion responds in words that have a forceful ring of truth. She tells MacKinnon:

“I said that after a lifetime of looking ahead to the bump in the road—or as I always thought of it, keeping the snake on cleared ground—I didn’t see how I could stop now.”

Jan Harayda is an award-winning journalist and critic in the American South. She has been the book columnist for Glamour, the book editor of a large newspaper, and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle.

You might also like my piece for @Medium about Notes to John. It wasn’t a review but focused tightly on what the book reveals about literary success. Here’s a gift link to it.

Interested in whose nonfiction I like besides Didion’s? You’ll find capsule reviews of some of my favorites here.

Notes:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/may/02/my-friend-joan-didion-wouldnt-have-wanted-her-therapy-notes-to-be-published

https://www.thetimes.com/culture/books/article/notes-to-john-joan-didion-review-kg5b3xwl7

https://dokumen.pub/south-and-west-from-a-notebook-9781524732790-9781524732806-1524732796.html

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/joan-baez-i-am-noise-review/

I can see where AA would not have appealed to her or would have been a struggle because of her formidable, relentlessly inquiring intellect. In both AA and Al-Anon there's a measure of surrendering and stopping thinking and just believing and trusting. I can see how her proclivity to overthink would hindered her; that's what I am trying to say, not very well!

It was def easier in Didion's time to be a white female trailblazer. There just weren't as many others around or in the recent past. Also I'm not sure Didion would have the audience today she had then. There's not as much market for white (WASPY) literature--that's all I was attempting to say. I guess that's another Substack.