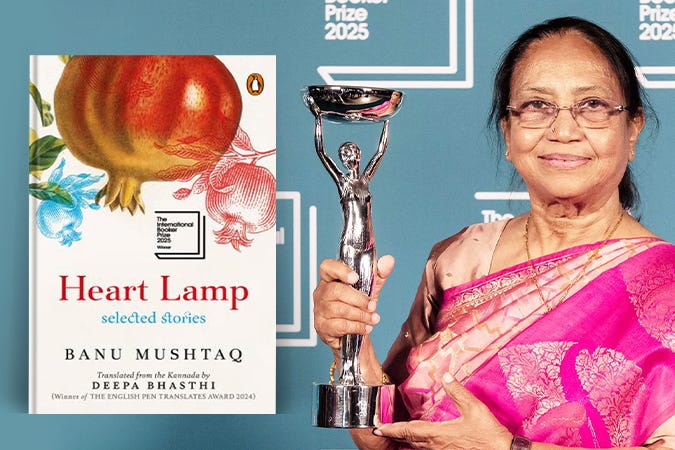

Three cheers for Banu Mushtaq's International Booker Prize winner

'Heart Lamp' tells fresh and surprising stories of beleaguered women and a mass circumcision of boys in India

Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp is a gem, but in order to appreciate its 12 short stories, you may have to get past the heavy payload of political cant dropped on it by the judges of International Booker Prize, which it won last week.

With no apparent shame, the panel said that book speaks “truth to power” and shows the “resilience” of oppressed Muslin women in southern India. Critics have fallen in line, praising its tales of “diverse” groups who resist the injustices of the “patriarchy.”

There’s some truth to all of this, just as there is to the talk about the milestones the prize represents. Heart Lamp is Mushtaq’s first full-length book to appear in English, the first short story collection to win the International Booker, and the first winner translated from the Kannada language.

But there’s an irony to the political spin. Mushtaq’s women struggle so fiercely for dignity and self-determination—if not for their lives—that time to think about the ideologies they represent would be a luxury. They’re fighting just to survive poverty, cruel husbands or in-laws, their lack of access to birth control or higher education, or other hardships. Their stories read not like academic treatises but brutal fictional dispatches from the front lines of a war against women waged by family, religious, or cultural authorities in their homes, mosques, and villages.

The word “patriarchy” appears in Heart Lamp only in an afterword by translator Deepa Bhasthi, who shares the £50,000 International Booker Prize with Mushtaq. And something like organized resistance to male tyranny surfaces in only one story.

In “Black Cobras” an abandoned wife begs a local religious administrator to help her persuade her husband to provide food, money, and medicine for their seven children. After he spurns her request, tragedy strikes, and the woman’s neighbors target the bureaucrat as he walks through their village. One curses him, shouting, “Nothing good will come your way…may black cobras coil themselves around you.” He can’t punish so many women, nor can he stop the deserted wife from making a private act of defiance to subvert what men expect of her.

Mushtaq’s women more commonly try to resist injustice privately, and they pay a scalper’s price for it. In title story, a lonely wife travels with her infant to her parents’ home, hoping for comfort after her husband leaves her for another woman. She tells her family she will set herself on fire if they force her to try to reconcile with him. But her eldest brother scoffs at her pain:

“Those who want to die don’t walk around talking about it. But if you had any concern for this family’s honor then you would have done that instead of coming here.”

The brother tells the heartbroken mother it’s up to her to make her marriage work. She has it better than women who have drunken husbands or mothers-in-law who beat them, he says:

“Thank God you are in a good situation. He is a bit irresponsible, that is all.”

In such scenes, the dialogue can sound a bit scripted, too neatly tailored to its plot. Mushtaq tends to make her points with less elegance than do better known writers of Indian ancestry, such as Jhumpa Lahiri and Salman Rushdie (though some of her stories have a touch of the phantasmagorical that may nod subtly to his magical realism). But her stories have the ring of truth, and they make clear that rich and poor women of all ages feel the sting of subjugation.

A barber’s mass circumcision of boys

In “Red Lungi” a well-to-do wife finds herself at wits’ end when expected to care for too many visiting children during a summer vacation. Razia decides she needs “to engineer bed rest for some of them” and comes up with a scheme that sounds like the premise for a comedy called “Monty Python and the Mass Circumcision.” Some of the boys underfoot will be circumcised at home, anesthetized by a private doctor. A barber with a shaving knife will do the job on boys from poor families, without anesthesia, at a madrasa, and reward them with food, rupees, or both afterward.

It says much about Mushtaq’s skill that she makes this setup not just plausible but poignant. An inflection point occurs when an impoverished mother tries to have her son circumcised a second time to receive the food or cash benefits. The woman is turned away when her desperate ruse is discovered. But Razia appears to feel guilty about the poverty she’s seen and tries to atone by giving a poor boy unopened clothes her son received as gifts for his own circumcision. The recipient accepts them with more than gratitude: “a sense of devotion.”

As a group, Mushtaq’s stories expose the ways in which women remain second-class citizens or worse. In that sense they resemble some of the fiction that fueled the second wave of feminism—novels like Fear of Flying, The Women’s Room, and Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen—though worlds apart from them stylistically and geographically. Mushdaq’s collection exposes injustices as bluntly as those books did, and it’s a worthy and surprising Booker winner when too many major literary awards are drearily predictable choices that rubber-stamp bestseller lists. Heart Lamp leaves no doubt that Mushtaq deserves a wider Anglophone readership.

Jan Harayda is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book editor of a large U.S. newspaper and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle. Her reviews and other articles have appeared in many major media.

Want to read about more great short stories? Join the conversation about “The Lottery” that and I are leading in this month in our short stories club on Substack. Or check out last month’s discussion of Chekhov’s “The Bishop.”

It sounds like she's just telling a story, showing life as she sees it and letting the details speak for themselves. Not that that is easy! It's not. But it is far more powerful than proselytizing.

Heart Lamp is on my list!