Letter from a Reader 6.9.25

Is Susan Choi's 'Flashlight' really 'the first major American novel' of 2025? Plus Rick Atkinson and Ernest Hemingway

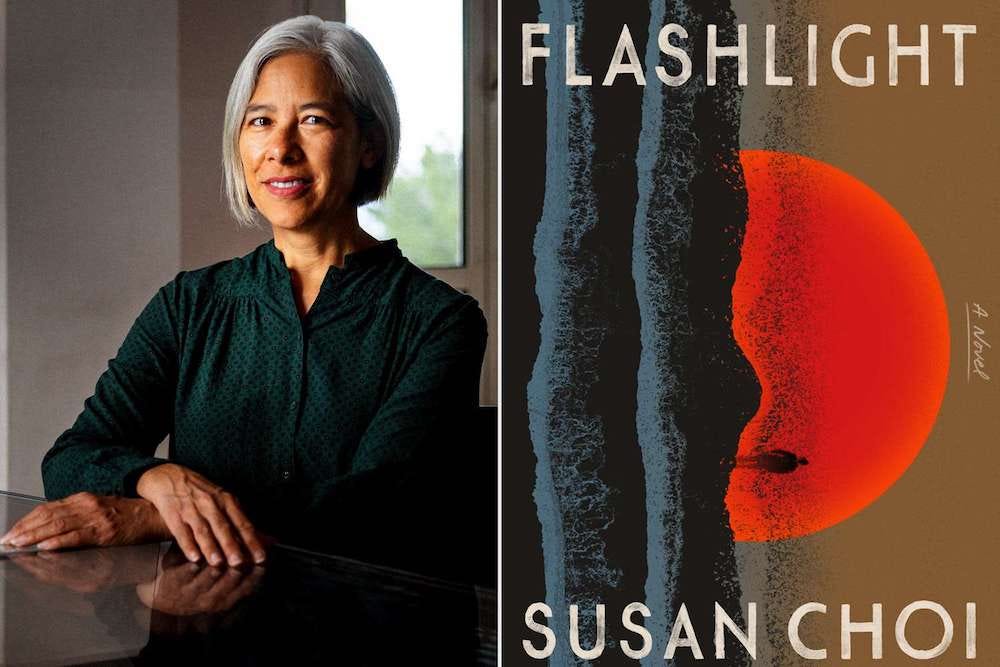

Over the weekend the critic Sam Sacks called Susan Choi’s Flashlight “the first major American novel to be published this year.” I tune out words like those when they come from publishers or from reviewers too eager to crawl into bed with the lead titles from Knopf or Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

But Sacks is an unusually trustworthy critic. He’s written a column about new fiction for the Wall Street Journal for 15 years, and I try not to miss it. His brief reviews are brisk, literate, and fair-minded: Sacks has written for the liberal New Republic as well as the defunct neoconservative Weekly Standard. And his columns are mercifully free of hype, clichés, and Nostradamus-style predictions (“you’ll laugh till you pee”).

So when Sacks said Flashlight was a major novel, I took note. A radio station in my area has been strafing listeners with commercials for something called the Wendy’s Son of Baconator, and Choi’s book lodged in my mind, irrationally, as “the son of that literary Baconator, Percival Everett’s James.” Could a Pulitzer be far behind? How about spot on the New York Times’ best books of 2025 list? Yes, it was a long shot, given that Choi’s book is from FSG, and 80% of the titles on the Times 2024 list came from Penguin Random House, but who knew?

I couldn’t finish James, but Sacks’ and other reviews had facts that made Flashlight sound more promising. The plot centers on an ethnic Korean man who vanishes during a nighttime walk with his 10-year-old daughter in Japan in 1978. It spans four generations of his family. And it involves egregious historical injustices to Koreans.

One of the most memorable nonfiction books I’ve read in recent years had centered on cloak-and-dagger defections from North Korea: Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy, which won the Samuel Johnson Prize for nonfiction. It left no doubt that there were more great stories about Koreans to be told, and I could see why Sacks called Flashlight a “major American novel” after downloading the generous 75-page free sample. It’s a big book, with big themes, from a big author, who won a National Book Award for her novel Trust Exercise. Yet I didn’t fall in love with the sample.

‘It doesn’t rev up right away’

Some reviews had said that the pace drags in the early sections of Flashlight. No kidding. “Eventually…the plot does kick into gear,” Sacks wrote, and Kirkus asked you to “give it a chance, because it doesn’t rev up right away.”

But the plot hadn’t revved up by the end of my 75-page sample. Why, I wondered, should readers have to forbear for so long when Flashlight has a list price of $30, the Kindle edition costs more than most paperbacks, and FSG has editors? Editors are often blamed for things they can’t fix, such as irredeemably bad writing. A languid pace is something they can improve by requiring writers to cut or shorten passages that are redundant or irrelevant or go on too long.

Then there are the tricksy literary devices in Flashlight. If you didn’t know Choi had a degree from one top-tier creative writing program, Cornell, and teaches at another, Johns Hopkins, you’d have figured it out within a few pages.

Flashlight begins with one of the devices most overused and, consequently, most loathed by many critics and readers: the italicized flashback. It goes on for nearly two pages. The book then rolls out another overused device: a switch from present- to past-tense narration. If you read a lot of literary fiction, you can probably guess what comes next: a switch from one character’s point of view to another.

Any of these devices can work well in a novel, and if you savored the third-person present-tense narration in Wolf Hall or the alternating perspectives in Gone Girl, you may like them in Flashlight. But their use gave me pause. Such devices can amount to a capitulation by an author who says, in effect, I couldn’t figure out how to tell this story using the omniscient or first-person narration the story needed. It didn’t help that Flashlight has jabs at “American imperialists” abroad when I’m already seething about the imperialism in the White House. Did I want to sign on for more?

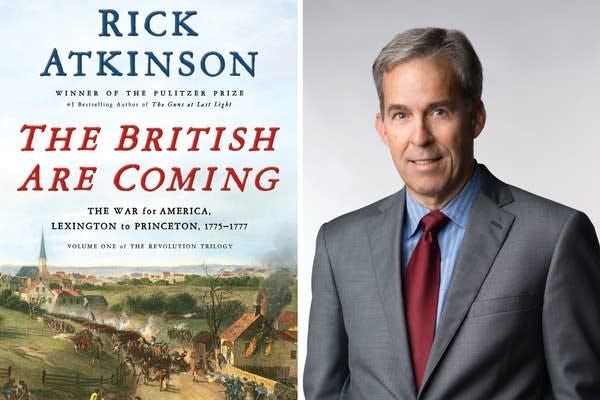

Most of all: Flashlight faced Hunger Games-level competition from other books on my nightstand, including the latest by Rick Atkinson, one of America’s great writers of popular history.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Jansplaining to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.